Wealth & Health App

Created and implemented user research strategy

I. Context & Background

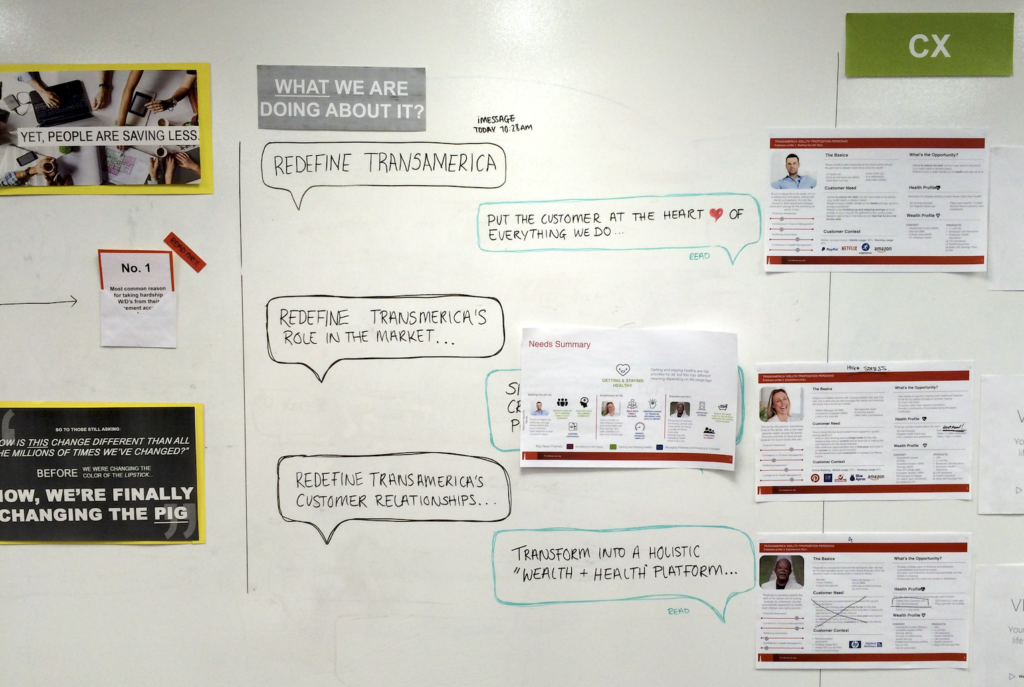

In 2016, I kept hearing rumblings in my company about “the new CX” that was being envisioned as a blank-slate project which aimed to fundamentally alter how we interacted with our customers. Where most financial companies were still providing users with simple metrics like plan balance and rate of return, Transamerica took a novel stance in the marketplace to incorporate health as a critical factor in one’s retirement readiness. The concept was this: if we know that healthcare costs in one’s retirement are projected to rapidly increase with age, why are we not addressing this critical fact with customers? We sought to simultaneously re-brand our company’s messaging strategy with a suite of new customer touch points, the mobile application being the flagship property in this new world.

I joined a project which had been allocated $30m over two years for the complete overhaul of core customer digital experiences. I took on the role of user experience (UX) strategist, splitting my time between business proposition design and tactical user research. Ultimately, my goal was to first work with colleagues to decide what we were going to build, and then to design and execute a user research strategy throughout all stages of the product lifecycle (proposition, design, development) while serving the “CX” product, which later evolved into a mobile application.

II. Objectives

While the introduction of health in one’s retirement journey was a novel problem that we had identified, that only tells half the story. The business purpose in introducing this new concept was to increase the wallet share of customers across our product lines. We knew that the financial services business had become commoditized—price competition was so intense that we couldn’t promote our pricing, service competition was strong because of how heavily regulated the industry was—so we had to get creative about our business proposition. Ultimately the drive to increase wallet share was a business decision that sought to help customers rely on Transamerica as a one-stop shop, the logic being that providing holistic financial wellness advice would be the connective tissue incentivizing customers to have retirement, insurance, and investment accounts under one roof. Our health proposition was the lynchpin of this new strategy.

The KPIs of the project were:

- Increase assets under management (AUM) through an increase in total customer wallet share

- Increase NPS through cutting-edge digital experiences

- Increase sales revenue through health-enabled content

Where did I fit into the bigger picture? As UX strategist, I was tasked with developing and maturing the value proposition that we would use in our go-to market plan, as well as the logic underpinning why we were embarking on the project. I focused my time on answering some very large, open-ended questions for the duration of the project, such as the “why” of what we’re proposing to build, and the “what” that actually gets delivered to customers.

I did this by building my understanding of the market, our customers, and our competitors to clearly explain the unique value that our product was poised to bring. Whenever we came to a crossroads in our product roadmap, it was my job to advise on which direction to take. This was usually done in the form of research reports, presentations, and persuasive memos. Ultimately, I sought to better understand who our customers were and how we could satisfy their needs.

My personal objectives were:

- Define the problem we intended to solve, incorporating real user needs

- Analyze what competitors are doing and make recommendations

- Build personas and map out customer journeys; connect those journeys to product decisions

- Generate ideas to bring to fruition

- Collaborate with UI designers to produce testable wireframes

- Make hypotheses about consumer needs; commission original user research to validate them

- Conduct usability testing of interfaces to ensure designs were well-received

- Drive business value through the satisfaction of KPIs

III. Methodology

Innovation through Design Thinking

I will admit that I began my journey into UX strategy with little knowledge of how to do my job. While I understood the fundamentals of UX—given my background in web design and content management—it was unclear to me how to apply them to the creation of a new product. One of the benefits about the project was the fact that we partnered with Deloitte Digital, who provided a working model and critical project guidance to those of us who were less experienced. We applied Design Thinking, which is a common framework for developing new products and ideas.

Ultimately, in designing a new product you must align customer problems to tangible benefits that your product seeks to solve. Design thinking allows you the opportunity to “blank slate” many concepts by walking you through a set framework where you seek to understand user problems, define those problems, ideate, prototype, and test them. I spent most of my time working on all of those stages except for prototyping, which was usually handled by UI designers.

Step One: Understand the Customer

One area in particular where I excelled was in-person user research. Each time we needed to validate the inclusion of a new product feature, the UX team and I worked behind the scenes to bolster and validate the assumptions made by the product team.To start, we began talking to real-life customers in a series of informal group discussions where we asked them about financial challenges they were having in real life. Later, I commissioned a series of focus group discussions where I introduced the group to topics on retirement. Were healthcare costs too high? Did customers understand the importance of saving for retirement? Were they saving enough? The key to developing a robust focus group conversation, I learned, was to actively listen and say very little. As long as the conversation is moving forward, you’re doing your job.

After the focus groups concluded, we began building out user personas that captured the market segments we were trying to target as well as the customers we just had spoken to. We compiled their wants, needs, and pain points, and built unique personalities into each of them. This allowed us to abstract our learnings into concrete examples. We drew on our knowledge from the focus groups as well as statistical analysis which incorporated data points about our customers that a discussion group could not uncover, such as average age, retirement likelihood, income, and other critical data points.

Step Two: Define the Problem

From the learnings we made in Step One, presented my findings to the product team. We spent dozens of meetings talking about how these customer learnings translated into real user problems. “Surely, people know the amount of money they should be saving on healthcare costs,” one product manager quipped. “Don’t they read our emails?” he continued. I replied with the findings from our report, “Despite our attempts to educate people, there is still a lot of confusion on the subject.” This conversation developed into identifying one of the more important problems of our project, which was getting people to think about the long-term effects of healthcare spending no different than retirement savings.

During this time, I compiled many additional research reports outlining the nexus between user problems and concrete insights. Interestingly, we learned that most customers were aware of the importance of certain topics, but this knowledge did not translate into user behaviors. People routinely described not saving enough money despite knowing it was the right thing to do. They were also not well-versed in the healthcare costs they may face in retirement. I recorded these findings and reported back to our working group.

The key output I helped develop from this stage was the problem statement, which is a concise statement designed to capture the user’s challenges. “As a customer, I need to save more money for healthcare costs so that I can achieve financial freedom” was one such statement.

Step Three: Brainstorm Solutions

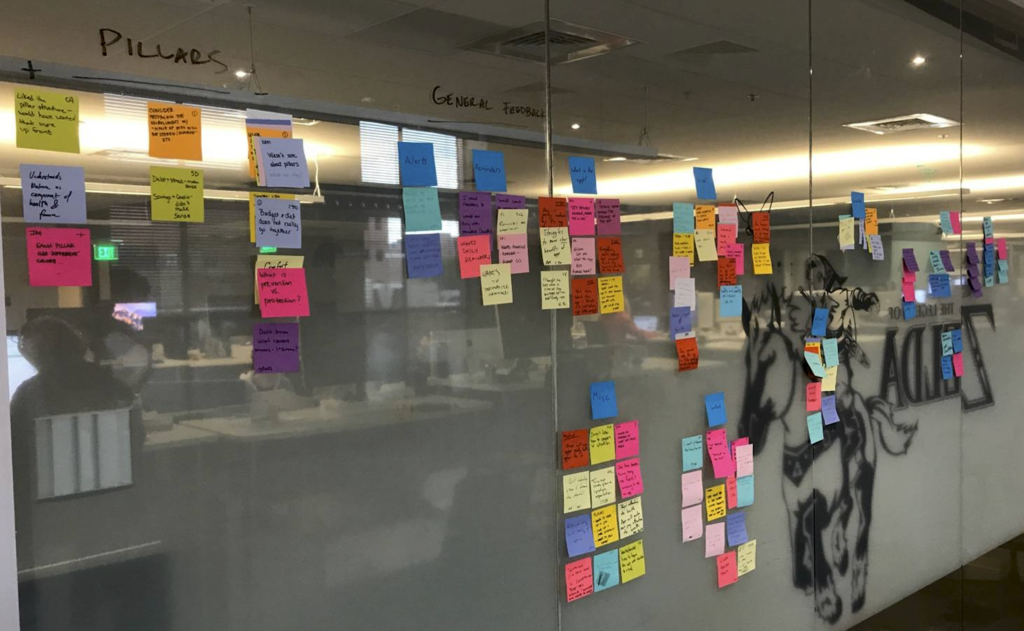

At this stage, we met with the product team and proctored ideation sessions where we encouraged everyone to think outside the box. We spent time looking for alternate ways to view the problem and identify solutions to the problem statement. For example, we asked all of the stakeholders to imagine themselves at the age of retirement. What would be some things they’d want to do with their time? How would they allocate their budgets? How would they cope with healthcare costs?

Usually we would set a time limit, like 60 minutes to complete an activity. We would pose a question like, “How do we help people build a budget.” This would focus the team to a single question. Answers were written on sticky notes and placed into categories on a whiteboard. This was very much an inductive exercise that can prove rewarding and intellectually stimulating.

As a UX strategist, one of my biggest responsibilities was to unlock the flourishing inside our team by encouraging weird and wacky ideas. This was supposed to be no-judgment space where any concepts were welcomed. I found that promoting the validity of all ideas before they could be vetted was a good way to collect as many of them as possible. In this case, quantity breeds quality.

Step Four: Build a Prototype

After we had gathered all of the ideas to build, it was time to select one to prototype. And what lists we would generate! Everything you could imagine showed up on our whiteboard, from virtual reality, to bodily trackers, to personal assistants. The next step before prototyping was to run the ideas through an analysis to determine feasibility.

One of my innovations as UX strategist was the creation of a holistic way to measure the “prototype-ready” status of an idea. As a team, I asked everyone to rate each idea in three categories: business impact, customer impact, and technical feasibility. Usually the last category was the big show-stopper for us, as the really high impact ideas were the most expensive. One of the ideas we settled on that had a high business and customer impact with a medium level of technical feasibility was a next best action (NBA) engine which would power individual user goals, allowing us to show users what concrete steps they should take next while using the application. For example, if someone had a high level of credit card debt, the NBA engine could offer guidance to pay down that debt first, as it usually carries the highest level of interest.

With regard to the actual designs, I occasionally drew up wireframes for testing which were handed to UI developers. From there, we tested our concepts.

Step Five: Test the Product

My role throughout Step Five was deciding what to test, how to test it, where to test it, and drawing conclusions from test data. Often this would culminate with me being referred to as a thought leader within my organization because I was able to confidently and accurately site the results of studies as a way to bolster the arguments that product managers were making. I gained a reputation of being the “go-to” person for answering novel questions, and the process of answering these questions drove my increasing level of expertise.

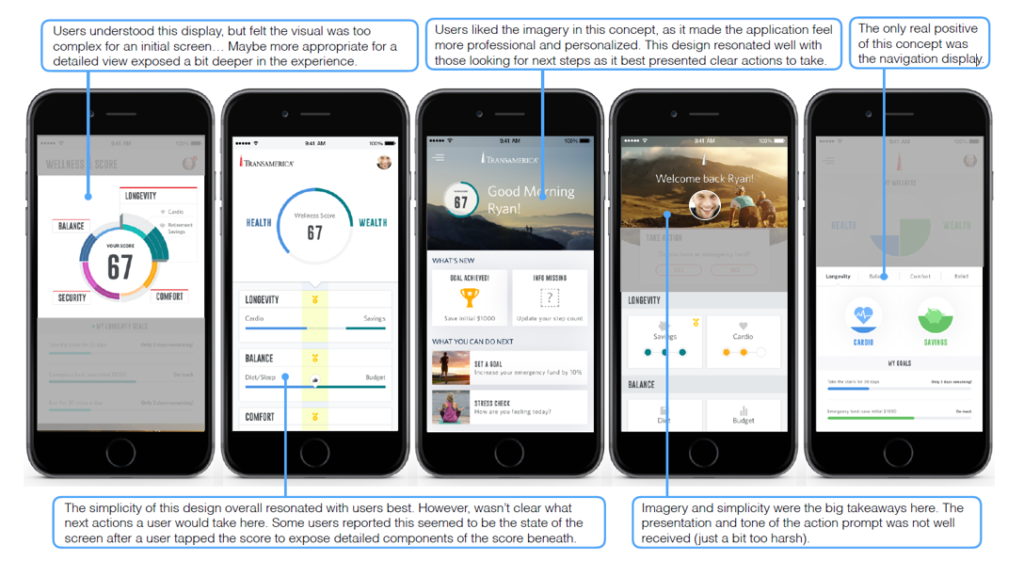

I focused on several types of testing: quantitative, qualitative, and usability.

I first would build quantitative studies to gauge user sentiment about new features. After that, we deployed qualitative testing to “drill down” on user sentiment. In situations where you need large quantities of data, a quick survey can go a long way. I conducted remote studies on platforms such as Usertesting.com and Userzoom. For example, we had a question about what names to assign the four “pillars” of our web application. Each pillar was designed to address a unique area that the user was to focus on. We wanted the names to be descriptive, aspirational and functional. I commissioned a round of quantitative surveys where I asked customers what their associations were to specific words and whether these aligned with our team’s goals. Based on our customer feedback, the final names we chose were longevity, balance, security, and freedom. This is a good example of using data to make critical customer decisions.

Moreover, I was directly involved in planning and executing usability testing. In one case, we needed to find out how our existing web experience was performing in comparison to what we were building. I commissioned usability tests that incorporated heat modalities such as heat mapping and eye tracking to determine the success of our interfaces. I compiled the reports which incorporated metrics from SUS, time on task, and fallback rate, to name a few. Having quantifiable results for our software interfaces allowed us to make informed decisions.

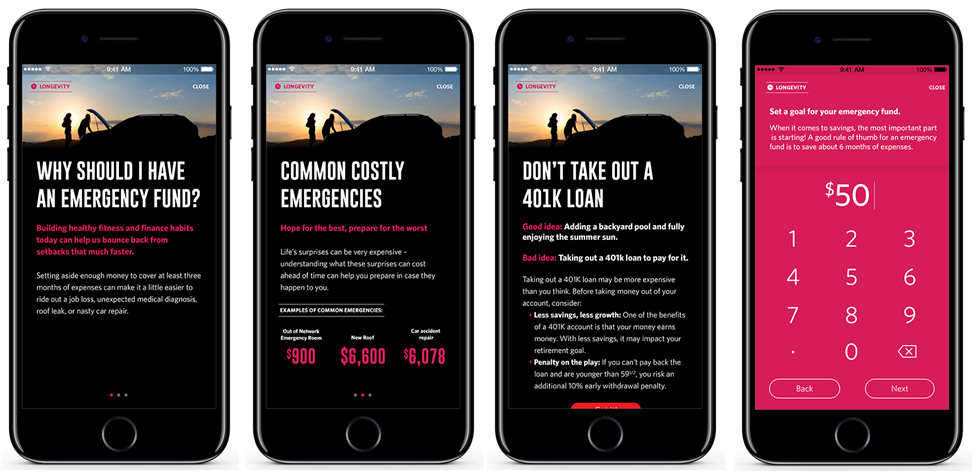

Typically, I kept the qualitative studies to less than seven participants, as research has shown that to be a sufficient data set to capture approximately 80-90% of user sentiment, assuming you recruit the right users. Qualitative studies I found the most engaging, given your proximity to the customer. For example, there was a question about whether the onboarding process into the app was effective. I hosted several sessions with live users in a laboratory setting. We set up a mobile device in front of them and began recording audio and video. I observed them walk through the onboarding journey prototype we were building. After that, we brought them together for a focus group discussion. Our question: would they aggregate external accounts? My research found that users agreed that account aggregation was a critical feature of the product, thus validating our current efforts.

Synthesis

When testing was complete, I handed my findings to the product team. This resulted in a virtuous cycle of improvement where we were constantly developing features and products that survived the scrutiny of the design process, giving us exceptional results.

IV. Results

During the length of the project, I served as an enabler; I helped the product manager and wider team make decisions. It can be difficult to quantify that impact, but I will say that key stakeholders consistently relied on me to produce these artifacts, and almost always rolled up the findings into reports they produced for senior management. I enjoyed many experiences of “hey, that’s my slide!” as I encouraged stakeholders to not be shy about taking my direct findings and using them to advance policy. Ultimately, this experience gave me good insight into what it takes to be a successful product manager.

My time as a UX strategist was prolific; I published over 20 user research studies during my tenure which directly impacted product features, such as: menu design, feature inclusion, page ordering, onboarding screens, imagery, interface design, roadmapping, feature development, prioritization, component naming, and market research. In numerous occasions, my research saved the team both time and money because we didn’t merely go with a hunch in making decisions; we had the research to back them up.

The app launched successfully and is currently available to 4m plan participants.

V. Reflection

The knowledge I gained as a UX strategist has been instrumental in building a foundation of sound research and analysis in my skill set. Moreover, it introduced me to a new methodology in how I approached problems. Instead of jumping to solutioning, it’s important to spend a great deal of time truly understanding the problem. A huge portion of this understanding comes from genuinely listening to and understanding customer needs. Without this critical step, your product will fail. I would go as far to say that this methodology has even been beneficial in my general life, benefitting me in ways that I cannot merely credit to my career.

Furthermore, the working relationship I developed with product managers developed into lasting mentorships. Ultimately, my job was to help the product manager more clearly articulate the product vision through consumer research. This led to a virtuous cycle of improvement where my findings were incorporated into the project roadmap and beyond.

View Other Projects

© 2022, jcgreco.com