Funding cuts are a fact of life for product managers. There may be situations where you’ve taken all of the steps to plan, execute, and start building your product only to be told later that your budget is being reduced. Getting the money to execute your original vision was difficult enough. Having it taken away after the project is scoped can cause massive headaches for the PM, delivery team, and stakeholders.

This phenomenon happens across organizations large and small, and is one of the many variables that is outside the direct control of PMs. Sometimes business goals change halfway through the execution of a new initiative due to a change in strategic direction. Other times, the business has a budgetary shortfall due to its failure to raise enough revenue to sustain current commitments. This can create a downstream effect where all projects in the pipeline need to reduce scope to navigate the downturn. All of these scenarios put the PM in a precarious position.

Funding cuts may be caused by:

- Shifting goalposts. For example, the business has decided to focus on building a shiny new client-facing application that requires it to meet its SLAs, and your project is building a new participant-facing application.

- Business shortfall. For example, 10% of a company’s projected $50m revenue from the previous year was slated for R&D, but since the company only generated $40m in revenue, the R&D budget is cut by $1m.

- Divisional shortfall. For example, another project is facing cost overruns of $500k for the quarter and money is being diverted from all of the projects within your functional unit. Your project is asked to give up headcount totaling $100k.

Fight Back with a Plan

Fortunately, there are strategies you can take to mitigate the impact of budget cuts so that your end users and business stakeholders stay happy.

Start with Story Mapping

The role of a PM is to deliver value to customers through product offerings. One of the benefits to working in an agile framework (and this article assumes you are), is it lets you chunk work into smaller pieces over the course of an entire project. If done effectively, this strategy can be an effective bulwark against future budget cuts.

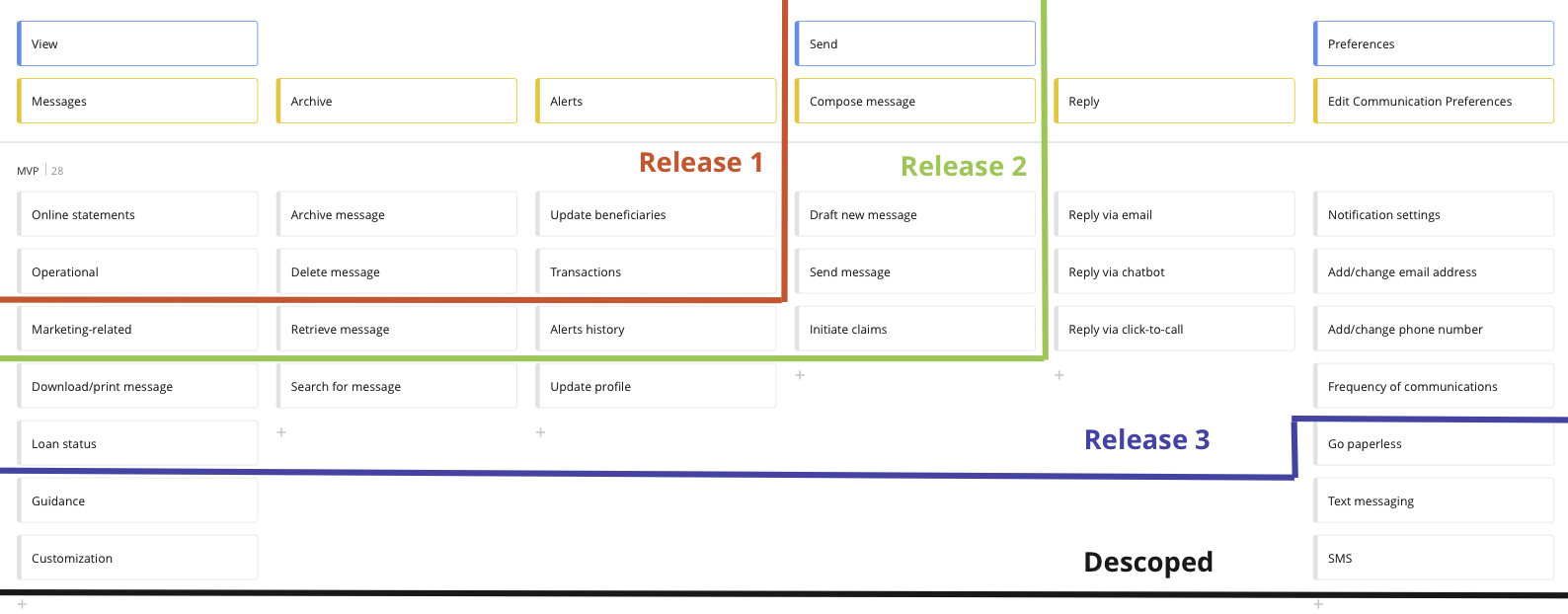

Let’s say you’re trying to build a new application that lets users send messages to customer service. In the user story mapping process, you (and ideally, the UX team) should have identified a user story map that depicts the overall work to be done in the form of a visual hierarchy, starting with themes at the top, followed by user actions, ending with individual granular interactions in the form of user stories. What I like to do is map the blue boxes to features/themes, the yellow boxes to epics, and the grey boxes to individual user stories. The features/themes should move left to right in order of how essential they are to users. The epics should be laid down in an approximate chronological order, while the user stories should be arranged in order of priority.

Here’s where the magic happens. After you lay out the story map, you should draw in the releases to show when you are planning on building these elements. This becomes a prioritization exercise where you can very deliberately include or exclude features depending on your budget and scope.

So, let’s say you’ve just released version 1.0 (hopefully with many accolades) and you’re gathering business requirements to build v. 1.5. The product director announces a substantial cut to your $5m project in the amount of $1m. You will be tempted to call a meeting and explain to the product director why he’s wrong, why you are right, and why you should keep the funding as-is.

Instead, you need to channel the spirit of Agile and de-scope the features that provide the least value. If you already have a story map, this should be an easy exercise. Identify the releases that are the lowest-priority on your story map and assess how much money you can save by cutting them. This brings us to our next task, budgeting.

Plan a Budget

The story map exercise is a good place to start because it can be easily shared with stakeholders and gives you a visual guide to start trimming the fat from your product. However, we still need to relate these individual features to budget projections.

As PM, you should have a budget file where you’re tracking the costs associated with your initiative. In the case of building an application, you will have ongoing labor costs–business analysts, front-end developers, back-end developers, QA, UX researchers, UX designers, all of whom have a set hourly rate and a set number of hours assigned to the project for the duration of the engagement.

One of the reasons that BAs are so valuable is that they work with PMs to flesh out product requirements into easily-translatable user stories that developers can start working on. They take your vision and ask a bunch of really difficult questions, the result of which is hopefully a well-explained Functional Requirements Document (FRD). During the analysis process, each user story will be assigned either a t-shirt size or story points, depending on your organization. We won’t get into the differences in those methodologies here, but they allow us to equate user stories to actual developer effort.

So, back to our original example, we have to identify $1m in savings from the project. Things can get difficult when you begin projecting costs for features that haven’t gone through the business analysis phase yet. Remember, in our scenario we’re in analysis for v. 1.5. How do we know the cost of v 2.0 and beyond? For starters, there should be high-level estimates that were decided upon at the beginning of the project. But they don’t answer the question: where do we come up with the $1m?

You’re going to have to huddle and try to come up with an estimate. Draw analogies to features that were already completed. Did they experience any overruns? Were there any services that needed to be built that did not get completed? Are there any legacy systems causing project complexities? Does your organization need to procure any external vendors? What is the team’s throughput?

So, you call a huddle with the BAs and developers. They estimate a feature slated for v. 2.0 can save $700k if you de-scope it. The feature is the least attenuated to your KPIs, and was initially added as a pet project for an executive who is no longer with the company. You aren’t too worried about descoping this feature because it was the least important in your project, and if you cut it, there will be minimal impact to the user. You also take out the Go Paperless feature from the preference center because it’s estimated to be $300k to build and the executive team is more focused on growth than cost-cutting.

“Voila,” you say, “I found the money and solved the problem!” While this may come as a relief, you’re not out of the woods yet. You still have to build organizational consensus around your decision.

Manage Stakeholders

One of the challenging things about product management is that products do not exist in a vacuum; there are always downstream impacts to everything you decide to build (or de-scope). These exist inside and outside the organization. Just when you think you’ve solved the problem of finding the $1m, new problems may arise as a result. During the next planning call, you get a question from someone on the brand team about eliminating the Go Paperless feature. They explain to you that the company recently signed a pledge to reduce its carbon footprint through the reduction of paper mailings. The elimination of your feature will result in the company not meeting its pledge, thus putting the brand team’s objectives at risk. This is a classic example of a downstream impact and unintended consequence that must be solved by the PM, even though the PM did not cause the problem.

One way to cut through this clutter is to build a visual roadmap and adjust it frequently. Share the link with lots of stakeholders–but be prepared to answer lots of questions! A product roadmap is something that helps you put everyone on the same page across the organization. If you maintain it on at least a weekly basis, it can serve as a central focal point for other teams to reference, thus allowing you to communicate your vision without calling extra meetings. It also prevents other teams from claiming that they were surprised by certain product changes. “Hey, did you see the roadmap I sent you?” is a retort that can shut those conversations down easily. However, in many situations a roadmap will not suffice. Often, PMs must raise high-visibility issues to many people across many teams.

So, back to our scenario. You’re trying to figure out how to de-scope this feature without upsetting brand. You set up a call with the product director and the brand director. The meeting has over 30 participants, all of whom are waiting on baited breath to hear what you have to say. You know that you’ve been told that expense reduction is a major focus. You also know that we have to uphold the obligations of the brand team. So, you make a novel pitch to the group by suggesting a middle ground: since you know the Go Paperless feature was going to reduce costs in the amount of $600k per year, and only costs $300k to build, you advise keeping it in the roadmap on the condition that the brand team contributes $150k to the initiative because they are also benefitting from your initiative. Brand has some extra money to throw around that quarter, so they happily agree to contribute to your project. Your boss likes the idea so much that he makes the decision then and there–that we’re going to keep the feature and uphold the obligation to the brand team. You’re still in the hole $150k, but your boss tells the CEO that the organization will have to find the missing money elsewhere.

This is a good example of how PMs need to utilize and refine their communication skills. Often they act as bridge-builders between disparate organizational units. They lead by consensus in everything they do, and this includes managing stakeholders.

Conclusion

The life of a PM can be one of shifting sands. There may be situations where your funding gets cut. This may at first be emotionally-fraught, because you’ve invested your time, energy, and creativity into building something new that you believe in. But you can’t let emotion get in your way.

If you invest your time in story mapping, this can go very far in helping you mitigate risk because it does much of the de-scoping and prioritization work at the outset. Once you do this, it will be easier to plan a budget. Use your knowledge gained from v. 1.0 to draw conclusions about how much money your proposed feature cuts will save. Lastly, don’t hesitate to engage stakeholders across the organization to come up with creative solutions. Ultimately, product development is an organization-wide effort, with you at the helm. Own your responsibility. A budget reduction does not necessarily mean your features will be lost. The next release will be here before you know it.