An invisible force lurks in the darkness, moving in silence. You think everything is going okay—and then it slaps you in the face. Is it medical debt? Postmodernism? Will Smith?

No—it’s internal stakeholder pressure.

It starts with a favor from a colleague on another team. “Hey, would you mind helping me out?” At first glance, it seems like a minor request. It’s “just” changing a single line of code in the application so that your buddy can meet his project goal. “It will be easy,” he says. To complicate matters, you face organizational pressure to accommodate this person because his budget was recently cut and your division has agreed to pick up the slack. So, you agree to do the favor. The code goes into the next sprint.

Weeks later, the UAT process finds a critical error from the new line of code that now is your team’s job to fix, siphoning off precious developer hours to clean up the mess. You miss your team’s release deadline.

In allowing yourself to be distracted, you’ve succumbed to stakeholder pressure and put your project at risk.

Who's a Stakeholder?

We’re defining a stakeholder in this context as any colleague whose work stands to be affected by your product rollout. This could include a fellow PM, a marketing manager, a sales manager, the director running the call center, the client executive, or even the CEO. Basically, it’s potentially anyone at your level and up the chain. Stakeholder pressure is a constant force that lives throughout the life of your project, coming in the form of evolving business strategy, pressure to change strategic course, and accommodating the diverse array of needs from across your organization. It’s different than scope creep, which is often the result of stakeholder pressure (if you allow your vision to be clouded and give in). Here we’re going to focus on what you will experience before the scope creep happens, and offer ways to stop it in its tracks. There are two types of internal stakeholder pressure: collegial and managerial.

Collegial pressure usually comes with a smile. Any time new stakeholders crash your project, declare their love for what you’re building, and ask you to start doing them favors, that’s stakeholder pressure. In this scenario, you will be asked to help other teams using your development budget. Here’s an easy tell: if someone asks you to “just” do something, head for the hills. Teams with funding issues tend to fall into this pattern because they need to augment their lack of budget with funding from other teams. If left unchecked, organizations can fall into the vicious pattern of teams regularly stealing money from one another under the guise of cooperation.

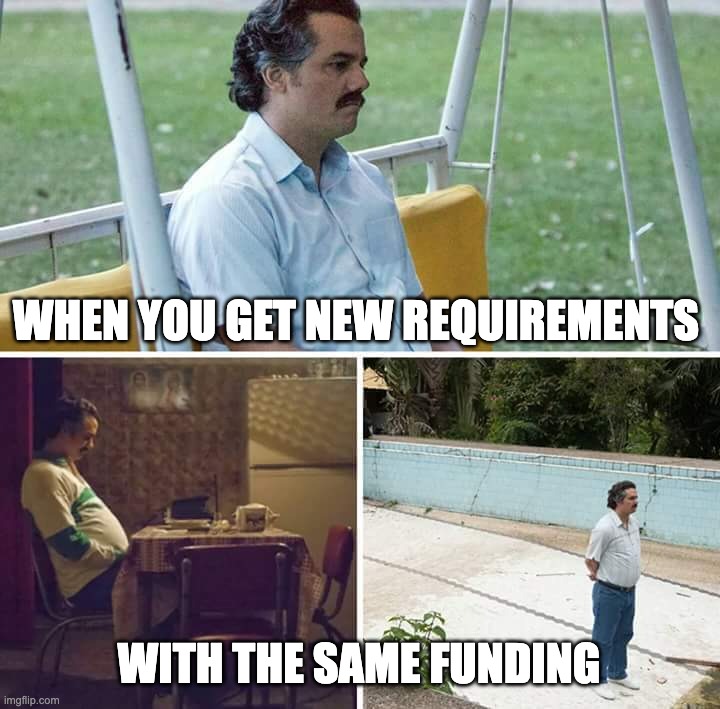

Managerial pressure is less subtle and more forceful. This type of stakeholder pressure results from senior management changing directions during the course of the project. Let’s say you design an application that plans to help people make no-fee cross-currency payments and you’re halfway through development. Your CEO visits a conference espousing the virtues of the upcoming metaverse. “This is a huge growth opportunity,” he says. “As of today, all new projects have to launch in the metaverse.” Facepalm. New requirements have formed after you’ve written the epics and user stories needed to launch your product. This type of pressure can be caused by a change of leadership, a change in (or lack of) leadership vision.

This is our last dance,

This is our last dance, This is ourselves under (stakeholder) pressure.

What's the Ask?

The first step in managing stakeholder pressure is to don your BA hat and start asking questions. “Just say no” may have worked for Nancy Reagan, but it’s not the best approach for you. There will be many situations where you must accommodate other teams for purely political reasons. This does not mean you have to give in to their every whim. If someone comes to you asking for a favor, you need to spend time scoping the size of the request. This is not much different than general requirements gathering, the difference being that you are potentially adding a new feature that was not in the original backlog, and therefore you may not have the time or resources to fully flesh out exactly what you’re being asked to do.

For example, say you are the PM of a post-login user experience with 4m users. Your goal is to migrate the website to the cloud, and you have 500+ user stories to deliver before that happens. Someone in R&D, on a very limited budget, is building a chatbot prototype and needs to test how the bot will behave in your web application. Their ask is simple: “Hey, can we install a single snippet of code into your page header, in the test environment?” You believe that chatbots are fundamentally a good idea. You respect the person who asked you and would like to help her out. But your current project’s funding is fully allocated. You have to deliver on your first release in less than two months. What do you do?

Conduct a cost-benefit analysis. If you install the code snippet and it messes up your test environment, you’re going to create a huge amount of work for the development team which could delay your launch. On the other hand, if you install the code snippet successfully, and the chatbot prototype gets noticed by the right executives, your team may get funding to build it later. Each situation requires a careful consideration of risk and reward. In this case, I would probably say “No.”

To mitigate stakeholder pressure, build out scenarios. Talk to your manager. Build organizational consensus about the urgency of the request. Do your due diligence and make the call.

Build Your Backlog

The best (and worst) thing about ideas is that they are free. As a PM, you’ll get plenty of would-be innovators knocking on your door, proclaiming, “Hey, wouldn’t it be cool if we…” The deluge of ideas will be a constant source of distraction for you. Suppose I told you there was a place you could save all of the awesome, brilliant, visionary ideas that are going to shape our world—like Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs—for later. Or never.

The moment you send an idea off to this magical land, your brilliant cross-functional innovators exclaim their unending appreciation for your time, go back to their day jobs, and never again bother you about their ideas. Is it Narnia? No, it’s your backlog!

One of the major skills you must master in product management is communication. Because PMs usually operate in flat organizations where they must drive organizational consensus, the ability to master the art of communication is a critical soft skill that you will work on over the course of your entire career. Not only does communication include the classical examples like giving persuasive presentations, speaking with clarity, writing effective correspondence, and pitching ideas, but also knowing how to manage stakeholders effectively.

That’s precisely what the backlog helps you do. It’s a record of all the “awesome” and “brilliant” ideas that stakeholders have offered you (I’m being extra cynical here: some of them actually will be brilliant) that you can store and manage in one central place. You can do this on a public board where everyone sees it. There’s nothing more flattering than offering someone a product idea and seeing him actually type it out and save it for later. In doing this, it shows that you are actively listening to stakeholders and considering what they have to say. Remaining focused on your product vision is important, but that doesn’t include ignoring everyone with an opinion. It’s a good middle ground strategy for PMs who don’t blatantly want to say “no” to a stakeholder, allowing him to consider the idea for later, whenever that date is. Now-pacified stakeholders will return to what they were previously working on. But they’ll be back.

For each backlog item, you should note the date of your conversation, the general idea of what was proposed, pictures, any supporting materials, and even an estimate of when the feature may work itself into your roadmap. You should get into the habit of periodically grooming it and ordering it by priority as well. You want to offload as much from your working memory as you possibly can. This will enable you to completely focus on the work at hand, and return to the backlog periodically to refresh your recollection of past stakeholder discussions. When the next sprint planning meeting comes up, take time to evaluate whether the new items you’ve added to the backlog would make good release candidates.

The backlog lets you collect, control, and classify the inevitable deluge of ideas that you will receive as a PM. Use it to your advantage to reduce stakeholder pressure. The backlog lets you collect, control, and classify the inevitable deluge of ideas that you will receive as a PM. Use it to your advantage to reduce stakeholder pressure.

Just Say "Yes, and..."

There may be times when you’ve met your match. An unusually tenacious stakeholder continues to press her viewpoint after you’ve clarified the requirements, determined that the request is too large to accommodate, and added her idea to the backlog. Your attempts to pacify her were unsuccessful. “No, this can’t go into the backlog. We have to do this now,” she exclaims. She’s gushing about how she’s made a commitment to the sales team. She looks at you squarely and says, “If we don’t re-write the application code to include a white labeling feature by the end of the year, we may lose millions of dollars.” Once again, your user-facing application is the website where all customers interact with the company, and is therefore in the cross-hairs. Don’t think it’s your problem? Think again!

The strategy to mitigate this type of situation is to adopt the “Yes, and…” approach. This allows you to set conditions about how, when, and where the product change is implemented. Moreover, it keeps you from saying “no,” however tempting it may be. Since product management is at its heart an innovative profession, and therefore a creative one, to flatly deny all requests is anathema to your purpose, and a risky move that could alienate many of your supporters. Instead, if you accept the request and place the necessary conditions upon it, you stay in control of the situation.

Unlike your Twitter feed, the corporate world is a more refined microcosm of broader society. If you lay out a rational argument to your colleague, who we are assuming is a consummate professional, there’s a good chance she will understand your perspective. You gently explain that it’s not the feature itself that is the problem, but rather the aggressive timeline for completion. You call a meeting and lay out all of the funding available by year’s end, the roadmaps, the KPIs, everything. You acknowledge the merit of what she is asking for, and lay out a mitigation plan to bring the work in at the start of the new year. She agrees to your plan, even though there will be a reduction in sales. The broader team agrees that given the facts, there was no better compromise.

In adopting a “yes, and…” mentality to stakeholder requests, you mitigate stakeholder pressure by taking control of the timeline and putting yourself in the driver’s seat.

Good Luck, Pablo

Internal stakeholder pressure is an insidious force that is constantly knocking on the product manager’s door. It’s something that must be constantly guarded against during the life of your project. If managed improperly, your product will fail.

By asking the right questions, building a backlog, and taking an active role in incorporating stakeholder requests, you will mitigate stakeholder pressure and keep your project on track.