Transamerica Chatbot

Led discovery team in building virtual assistant prototype

I. Context & Background

Our company stood at a crossroads in the development of virtual assistant technology. Competitors were gaining ground quickly and reaping the benefits of automation, cost reduction, and improved customer satisfaction. We asked ourselves why a chatbot had never been developed at Transamerica. The answer? No team had ever presented a compelling enough business case to receive funding from senior management.

In my first role as a product manager, I assembled a cross-functional team to take on the challenge. This was my first experience managing a small team and building a business case from the ground up. It was a rewarding experience that I’d like to share with you.

II. Objectives

Our mission was to develop a business proposition that saved the company in annual expenses. The initial ask made by senior leaders was a bit of a leading question, bypassing the usual UX process and going straight to the “solution” of building a chatbot. I was weary of developing a product without being able to truly own the problem, which is a best practice for building new products because it keeps open the possibility of genuine innovation.

“We need to build a chatbot,” the VP of digital said, clutching his phone. I replied with a counteroffer: “Let me prove to you it’s good idea to build a chatbot.” After some cajoling, he obliged. Getting the green light to work through the full UX process was important for a few reasons: first, research generated during the process would pay dividends for likely the next five to ten years. Second, understanding what users’ problems are, in addition to the problems faced by the business (namely, expense reduction), are critical in understanding how to deploy a novel solution. Third, it’s the right way to do things.

There are plenty of things that save businesses money that customers also like. Many people like to pump their own gas and check themselves out at the store. Yet, rarely do companies openly advertise the cost savings of these acts to their customers. In a store with both a self-checkout line and cashier line, there is no discount for choosing the former, nor is there a surcharge for using the latter. Similarly with a chatbot, customers may not understand that calling into the call center costs the company money that could be otherwise saved if the customer instead uses a chatbot. How can we ethically guide consumers into choices that both save the company money and give customers their preferred method of contact if we stubbornly assert that they “should all be using a chatbot” for our own benefit?

Call centers are expensive. Industry standards estimate that each call costs about $5 to $15 to service. Therefore, we speculated at the outset that the savings from automating this process would be immense. However, we must go back to our original question: would the proposed solution of a chatbot actually be well-received by users? Independent of whether a chatbot is saving a company money, the solution would have to stand on its own merits and simultaneously provide value to the user while saving the company money. That’s a good customer experience.

The KPIs of the project were:

- Figure out what users are struggling with

- Spin up a working virtual assistant prototype

- The prototype should be as close to “dev ready” as possible

- Demonstrate a clear business case

- Get it done within 6 months

As product manager, I ran a small team with a shoestring budget. We had a developer, a designer, and a project manager. I had the responsibility of defining a vision and making sure we were reaching our goals.

My personal objectives were:

- Learn how to run an effective Agile team

- Analyze the competitive landscape

- Delegate tasks to working team

- Champion team morale

- Take responsibility for success/failure

III. Methodology

Crunch the Numbers

Product development is a virtuous cycle where you must: (1) identify the problem, (2) propose a solution, (3) test the solution, (4) deploy the solution, and (5) continue iterating. To build a business case, we attempted to answer the following questions: (1) what is the cost per call, (2) how many people call us per year, (3) what are the upfront software costs to implement the bot and (4), how much money could we save by deflecting a percentage of those calls away from the contact center?

I met with our contact center and compiled a list of every phone call the company received that year. The file was so massive that it froze our Outlook client when we tried to email it unzipped. After analyzing the frequency and purpose of customers’ calls, I calculated how much each call was costing the company. This was done by calculating the cost of labor at the call center plus our overhead costs. It was about 90/10 in favor of labor costs as the larger of the two.

We met with our delivery partner, OneReach.ai, to discuss what could be expected if we deployed a chatbot. I asked them what would happen if we stuck the chatbot window front and center on the website. Would our total call volume decrease? How many customer problems could we actually solve without relying on human interaction? At this point I learned about the critical metric used in chatbot monitoring: call deflection. A company’s call deflection rate is calculated by taking the number of people who use the chatbot divided by the number of people who need assistance. You want to deflect as many calls away from the call center as possible by identifying the easiest scenarios that the chatbot can solve.

We settled on a modest deflection rate for our benchmark, which is around 10-15% for many organizations. We brought this deflection rate into the analysis as our ideal deflection rate, which we would test later with users. At this point, the overall structure for our business case was established: (1) we had a good estimate of how much money we would save using a chatbot, and (2) we knew how much money it would cost to implement.

Talk to Users

To get closer to our users, we set up panel interviews, surveys, and focus groups to understand why people contacted us. Could they not remember their passwords? Did they need help looking for a form? Did they just need our address? When we tallied up their responses, we found that many customers craved simple, quick-hit answers to a variety of simple things. For example, “what are your hours of operation?” one person asked. It wasn’t easily ascertained. “What is your mailing address?” Same problem. “When will my loan be processed?” There is simply no reason that these simple questions need to be answered by human agents in the call center. In fact, based on our findings, the customers overwhelmingly agreed. When we tested a sample chatbot prototype with users in small focus groups, the response was nearly universal. With the exception of a few holdouts, most people appreciated being able to get this information faster, even if it meant not speaking to a live agent. It was a convenience play, plain and simple.

Putting it Together

After our discovery work, the goal was clear. We were setting out with a vision that enabled self-service, reduced expenses, increased customer satisfaction, and improved our competitive edge. The goal for my team was to design, build, and launch a prototype in a test environment that would later be integrated into a larger IT project.

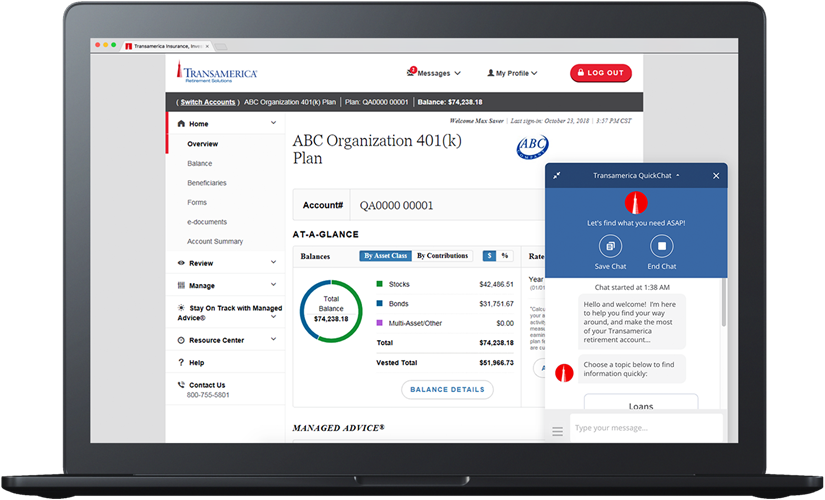

Next, we turned to building the prototype. The prototype was enabled by a lightweight Salesforce Einstein code snippet that we deployed to a home page in our test environment. The Salesforce agreement we previously had in place included Einstein as a paid feature, so we were actually able to bundle the cost into our enterprise technology fund, bringing our costs down even more.

The build process took several months. During this time, we built the chat dialogs necessary for the bot to converse with users. The information architecture of a chat dialog looks like a decision tree, where each potential response branches off into many different possibilities. Seeing what was essentially the mirroring of human conversation as a computer would see it was an interesting exercise into understanding what makes normal human conversation possible.

When our build was complete, we tested the prototype with users by facilitating usability testing with live customers. After several rounds of testing, we synthesized their feedback and made changes to the chatbot as required. For example, users wanted to speak more conversationally, and less formally, with our bot. We updated the chat dialogs as desired.

IV. Results

The chatbot prototype was met with a standing ovation at our introductory president. Our digital VP commended my team’s analysis and underlying research which was instrumental in getting the business case approved. Ultimately, the chatbot was approved by senior management as a “position one” initiative for the coming years, citing a seven-figure annual cost reduction through reduced call center labor.

After that milestone, my work in leading its discovery was complete. The project was handed to our offshore partners for the completion of the project. Within a short time, the chatbot went live to a production audience, and continues to be used by participants to this day.

Moreover, my business case research continues to be cited throughout the organization in new projects.

V. Reflection

This was an interesting project because it showed that, even though leadership may have preconceived notions about ultimately needs to get built, you still have to do the legwork of building a compelling supporting argument in favor of the desired solution. A product without the requisite user (and business analysis) is a house of cards that is doomed to fail.

As an early project in my product management career, it taught me the importance of defining the scope of the product by setting clear developmental milestones. Also, the unique opportunity to research, design, test, and implement our virtual assistant allowed me to grow professionally. I was given broad latitude to identify a problem and then find a solution for it. I directed a small team, defined the product’s features, interpreted users’ needs, built the overall vision, and managed its lifecycle.

I am proud to say that my vision became reality. That’s what product management is all about.